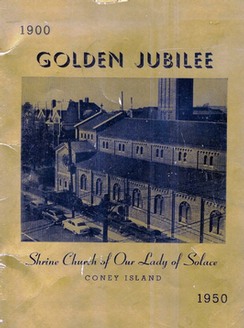

During the 1950’s, Coney Island went from bad to worse. With the death of Luna Park, all amusements on the north side of Surf Avenue but one, the historic B & B Carousell, were gone. The hotels had become fleabag and prostitution houses, bathhouses were seedy establishments, closing one by one, and national vendors on the Boardwalk like Howard Johnson’s were packing up and leaving. Most Coney Island amusement visitors were heading for New Jersey’s Palisades Amusement Park, or, for those wishing to stay closer to home, Rockaway’s Playland and Atom Smasher rollercoaster. One of the few bright spots at the time appeared at West 8th Street on the site of Dreamland, well away from the troublesome amusement area: the new New York Aquarium, which had relocated from the former Castle Garden in Manhattan’s Battery Park. (The building survives today in its original form as an 18th Century fort as Castle Clinton National Monument.) Although struggling, Steeplechase Park remained the clean, beautifully landscaped theme park it had always been, updating attractions to keep up with changing times and tastes. In 1950, under the stewardship of its pastor Rev. Merritt E. Yeager, the Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace marked the fiftieth anniversary of its founding by Dr. Brophy, as well as its forty-fifth anniversary as a Roman Shrine, by year-long celebrations and an enormous jubilee that was attended not only by local parishioners, but former parishioners from all over the country paying homage to the parish they loved so dearly.

By the time the second New York World’s Fair in Flushing opened in 1964, Coney Island was the last place to which families wanted to bring their children, having to literally escape the decrepit elevated terminal and violence-torn neighborhood for the safety of Steeplechase Park, Garms’ Wonder Wheel, and Ward’s Kiddie Land. Faced with the inevitable, the Tilyou family sold the Steeplechase site to Fred Trump and leased the property for as long as the Park remained open. For over a decade, the rich sound of the Meneely chimes had been silent at Our Lady of Solace, which could no longer afford to repair them. As a final gesture of the great generosity they had shown the parish since its founding, the Tilyou family had the chimes in the church tower repaired and overhauled with several smaller bells added and a new keyboard controller for the church’s organist in time for 1964’s Catholic Day. At the end of the season in October 1964, the Tilyous finally shuttered Steeplechase Park. Two chimes sounded in the park and, as the tower bells of the Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace sounded a death knell usually reserved for funeral Masses, the myriad lights of the last great original theme park went out forever. At one time, Robert Moses would have been celebrating his victory with the elimination of the last of Coney Island great theme parks. Instead, with his 1964-65 New York World’s Fair Corporation plunging into bankruptcy and saddling the city taxpayers with crushing debt, Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller had had enough of Moses. The controversial power broker had left a mixed legacy. In truth, he was responsible for some of the greatest public works projects of the 20th Century. As a child raised in the worst of the urban environment and later becoming a Olympic champion athlete, Moses had an honest and earnest desire to see children raised in the greenery and nature of the beautiful state park system, not the raucous and noisy settings of Coney Island, Canarsie Pier, Rockaway Playland, and Palisades Amusement Park. However, through eminent domain he also ruthlessly destroyed successful neighborhoods, such as Coney Island, and ruined an entire efficient mass transportation network on the verge of introducing some of the greatest technological advances in public transportation ever seen, in a borough and formerly independent city built around it. Moses’ “replacements” were half-finished clogged highways that were already obsolete shortly after their completion (such as the Brooklyn-Queens/Gowanus Expressways in Brooklyn, the Horace Harding/Long Island Expressway in Queens, and the never-completed Prospect Expressway that would have eliminated the main roadway of Ocean Parkway to the Belt Parkway). After the Fair’s closure, the master builder and power broker was himself broken.

Fortunately, there were many who would not give up on Coney Island despite of Fred Trump’s ambition to turn the area into a Las Vegas-style strip with legalized gambling and hi-rise entertainment palaces and hotels. Dewey Albert and his family purchased the former site of Feltman’s Hot Dog Emporium (where the frankfurter was originally created) to start a brand-new theme park called Astroland, cashing in on the popularity of the space-age craze started by NASA’s Mercury space program. The Cyclone, Tornado, and Thunderbolt rollercoasters (all independent attractions) shouldered on and the Parachute Jump, purchased by Norman Kauffman after Trump gave up on the Steeplechase property, continued dropping parachutes and riders from great heights. Kauffman’s new “Steeplechase Park” was pretty much a simple collection of carnival rides and not even on the old Steeplechase property. He did bring several items down from the New York World’s Fair after it closed that included several of the Fair’s lights and the Transportation Area’s Avis Antique Car Ride. The neighborhood’s seemingly out-of-control crime had finally made its way to the Boardwalk after the original Steeplechase Park closed and people were simply avoiding Coney Island in general. The Antique Car Ride was shuttered after the 1966 season.

Still refusing to give up on Coney Island, Tarrytown pushcart vendor, entrepreneur, restaurateur, and very frequent Coney Island vacationer Denos Vourderis purchased and saved the former Ward’s Kiddie Land in 1981. In 1983, he purchased the Garms family’s great Wonder Wheel as “…a wedding present to his wife - a ring so big, everyone in the world would see how much he loved her - a ring that would never be lost.” They were combined to form the ever-popular Deno’s Wonder Wheel Amusement Park. Starting with the Ward and Garms families and continuing with the current ownership and management of the Vourderis family, the park has been delighting children and grown-ups alike continuously for close to a century. It was during the 1980’s that interest in the shabby former amusement capital began to take shape. Coney Island had lost the Tornado bobsled-style rollercoaster to a disastrous fire in 1978; the Parachute Jump permanently closed the same year. The historic Thunderbolt ceased operation in 1982, and was illegally torn down on the orders of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani in 2000.

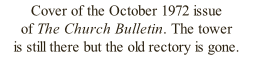

Often seen as a sign that Coney Island was about to turn the corner was in 1975, the seventy-fifth anniversary of the parish began with the discovery of the long-missing processional statue of Our Lady of Solace, found in the basement of a soon-to-be-demolished building; it had been stolen as prank in 1945 on V-J Day at the end of World War II but never returned. (Ironically, the clubhouse burned down a week later after it was found.) An external shrine was built for it by pastor Rev. Daniel O’ Connell. In later years, it was moved to the lobby of the school and replaced with the image of Nuestra Señora de Providencia (Our Lady of Divine Providence) as a tribute to the burgeoning Puerto Rican population in the parish. The parish itself, unfortunately, was struggling so badly that it could no longer afford to maintain its properties. The huge, aging, and mostly unoccupied rectory was a financial sinkhole for the parish and parking was at a premium. The parish elected to purchase a small lot next door to the convent on West 17th Street and build a smaller, more practical rectory and parish office instead. The old rectory was razed and the site became the main parking lot behind the church.

While community and amusements began to experience some re-growth, the natural sandbar that is Coney Island began to wreak havoc on the church and school buildings during the late 1980’s and early 1990’s when Rev. John J. Gillespie was pastor. In 1989, bricks began to fall of the landmark 185-foot bell tower. The church’s designer had attached the tower to the church building with the baptistery at its base and, failing to take underground streams and erosion into account, gave the tower a six-foot deep “square doughnut” foundation. With over forty tons of bells in its belfry, the top-heavy tower was on the verge of collapse, pushing against the church, causing cracks, fissures and unevenness to its floor, as well as cracks in the building’s walls. Fr. Gillespie immediately called in engineers to study the situation. The tower was condemned and the church immediately closed.

With the disused bells removed to the rectory parking lot, the tower was carefully disassembled and then rebuilt with 100 feet removed. Eventually two of the bells ended up in Vienna, Austria; the rest went to scrap. It had been the hope of Fr. Gillespie to eventually rebuild the tower and restore the bells, but with the church and school buildings aging badly and little financial support coming, it was no longer feasible. The parish was also suddenly rocked in 1989 by the sudden death of Fr. Gillespie at only 45 years of age.

With the untimely passing of Fr. Gillespie, Rev. Albert Bellantonio came to Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace to take over as the new pastor. With great personal faith and parish experience as a popular parochial vicar and administrator he served the parish for the next twelve years. He became known to parishioners and Coney Island as a great and enthusiastic teacher and ambassador of Catholic faith. With dwindling resources in the poverty-stricken neighborhood, Fr. Bellantonio always had an unflagging faith in and love for Coney Island, and the parish responded. Sacrifices had to be made; by the time the parish’s centennial arrived in 2000 the great Hilborne Roosevelt organ, last maintained in 1969, was no longer at all playable, and the condition of the church was in serious decline with care almost down to coming on an as-needed basis. Rising school tuitions and the dwindling presence in Coney Island of practicing Catholics saw school attendance fall so badly that by the time of its closure in 2003, it had only seventy-five students in attendance. The music ministry was practically non-existent, and choirs were borrowed from other parishes for special celebrations. Had it not been for to the efforts of Fr. Bellantonio, Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace might have finally been closed by the Diocese; it was on the danger list of parishes having difficulties in supporting itself. Nevertheless, Fr. Bellantonio piloted the parish through its joyous Centennial in 2000, and things were starting to turn around both spiritually and financially. By the time 2001 came, pastors were now down to term appointments. The centuries of the fifty-year pastor had come to an end. Now, a pastor would be appointed for a six-year term in a parish with an option for a second term, thus, a pastor could serve no more than twelve years in a parish. Had it not been for the mandated end of his term, Fr. Bellantonio would probably have been content to remain in Coney Island to the end of his days, and oversee the coming revival of the parish with the full support of his parishioners and friends. Sadly, it was not to be. Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace’s next pastor would set the historic parish on the road to new growth.

CONTINUE ON TO PART 6.