Over the decades, the destinies of the Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace and America’s Playground would be inevitably intertwined. Three years after the new church opened, the stock market crashed on October 24, 1928 to start the Great Depression. With massive unemployment, the lifetime savings of millions of people wiped out, and poverty and despair rampant, the always affordable “Nickel Empire” of Coney Island was one of the very few bright spots as millions came to the resort and amusement area as a temporary escape from their troubles. Although Coney Island had lost Dreamland to a fire that engulfed everything in the park in 1911, there were still the two other great theme parks (Luna Park and Steeplechase Park) as well as scores of independent attractions to satisfy the crowds.

The Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace wasted no time in doing its part in going to war against the Depression with a 24-hour soup kitchen, temporary housing for families in the huge rectory, and rallying the communities and nearby parishes in corporal and spiritual guidance. It became a destination for many as they made their way from the BMT Stillwell Avenue terminal and its myriad trains and streetcars. During this time, on October 4th, 1937, as he worked diligently in the parish office, pastor Fr. Kerwin passed away due to a sudden heart attack at the age of 62. He was Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace’s longest-serving pastor, having served for 23 years and responsible for the parish’s much-loved reputation as the “Parish of Processions.” Fr. Kerwin’s successor was Rev. Francis A. Froehlich, who served the parish as its pastor from 1937 until his death on July 4th, 1949 from a stroke at age 54.

When the Great Depression finally did end in 1939, however, there were even greater clouds on the horizon for Coney Island. There was little time to rejoice after World War II sprang up in Europe with the rise of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. The New York World’s Fair opened in Flushing Meadows adjacent to Lake Success (today’s Meadow Lake and not to be confused with the Nassau County village of the same name) and immediately siphoned off more than half of Coney Island’s visitors over its two seasons of 1939 and 1940. This was great news for master builder Robert Moses, who detested the raucous and noisy freak shows, rides, and perpetual carnival atmosphere of Coney Island. He wanted to eliminate them (preferring the clean and quiet nature of the Long Island State Park System he had created) and replace the farms and summer bungalows with a modern hi-rise community in the surrounding rural areas of Coney Island past West 19th Street. Moses also worked to put an end to Brooklyn’s burgeoning mass transit system of streetcar and elevated lines on which the BMT Company, much to his alarm, was introducing new and advanced technologies that would later become standard all over the world. Helping to force the IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit) and BMT companies into bankruptcy, Moses, with the short-sighted backing of Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and the devotion of General Motors, started his unpopular campaign of “urban removal” with the elimination of streetcar lines and elevated lines and the discarding of BMT technology patents, feeling that they were “…old-fashioned and worthless.” Through the newly-formed New York City Transit System, he then proceeded to force gasoline and diesel buses on the people of Brooklyn that they overwhelmingly opposed (93% to 7% in a Daily Eagle survey of 250,000 Brooklyn residents). (The transit patents that Moses and LaGuardia tossed away would have eventually had a value of a half-trillion dollars.)

The Tilyou family of Steeplechase Park had their eyes on one particular attraction located in the Amusement Zone (Great White Way in 1940) of the World’s Fair: the 250-foot high Life Savers Parachute Jump. Originally designed after a training device for paratroopers in Fort Dix, New Jersey, it was acquired by the Fair Corporation with Life Savers as a partner and sole sponsor. After the Fair closed at the end of 1940, the Tilyous purchased it from Life Savers and it was moved to Steeplechase Park near the Boardwalk, actually making sure it was in the same sight line as the landmark bell tower of their beloved family parish church, Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace. Together they became recognized landmarks by visitors to Coney Island. When the United States entered World War II with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Coney Island experienced a huge resurgence in attendance during the summer of 1942 to both its most popular attraction (the beach) and parks. As it always had done from its beginning, the Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace welcomed thousands of immigrants to its doors, mostly refugees who had successfully escaped the War in Europe. Like during the times of the Depression, the church was a focal point of Coney Island, a central point for organizing the various food drives, fuel rationing, scrap metal and rubber collection drives, and a foreign aid center for refugees. The year 1942 would be a high water mark for Coney Island and Our Lady of Solace, but the precipitous ride downhill began in 1944.

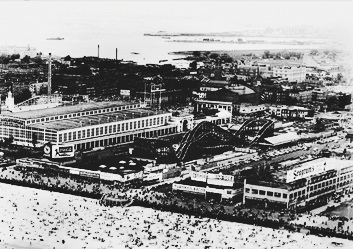

Frederic Thompson and Skip Dundy’s original Luna Park had been struggling for several years by the time the summer of 1944 arrived. It was still very popular (Walt Disney was a Luna Park regular every time he visited New York City; it served as much of his inspiration for many of the the attractions in Disneyland), but many of its live performance attractions were waning in popularity. The horrors of the war were hitting home and re-enactments of events like the Great Quake of San Francisco, the Burning of Atlanta, and World War I battles were no longer entertaining to the crowds. With the arrival of Robert Moses’ Shore Parkway and the rest of the Belt Parkway system (Shore Parkway, Southern Parkway, Laurelton Parkway, Cross Island Parkway) as well as the Long Island State Parkways, people were discovering the automobile and the suburbs of Long Island in earnest, as well as Moses’ crown jewel of Jones Beach State Park and its family-oriented cruise ship theme. The ultimate disaster came on August 12, 1944, when Luna Park was almost entirely destroyed in a massive fire. It did reopen with a walkway for visitors to see the ruins for a dime, and a few small rides were added, but it closed permanently in October. Moses immediately arranged for Thompson and Dundy to sell to developer Fred Trump and his group for the building of low-income housing towers on the site.

After the War ended in 1945, war-weary returning veterans and their families were looking for quieter and cleaner sources of recreation, and the noise and fast pace of Coney Island didn’t fit the bill. They were using their G.I. loans to buy cars and houses out in the Long Island suburb and townships and villages, preferring the tranquil atmosphere of Robert Moses’ State Parks and not the filth of the decaying Stillwell Avenue station and surroundings. Poverty, prostitution, drugs, and gang violence were things mostly unknown to Coney Island even in the days of Prohibition. Now they descended on Coney Island like a plague, almost encouraged by Moses in order decimate property values and create urban blight throughout the 1950’s and 1960’s. That way, the City could get federal money for redevelopment and Trump could secure the building contracts for the hi-rise housing projects.

As Coney Island suffered, so did the Shrine Church of Our Lady of Solace as well. The excellent school was not only a place of learning for its students, but an oasis of God’s love and calm among the chaos that surrounded it. As neighborhood poverty grew, the parish became more and more financially strapped over the years and parishioners volunteered to step in and help maintain the property and buildings. However, its presence in the community became even more pronounced and it became an even greater sign of God’s presence in the declining amusement and resort area as the parish’s golden anniversary approached in 1950.

CONTINUE ON TO PART 5.